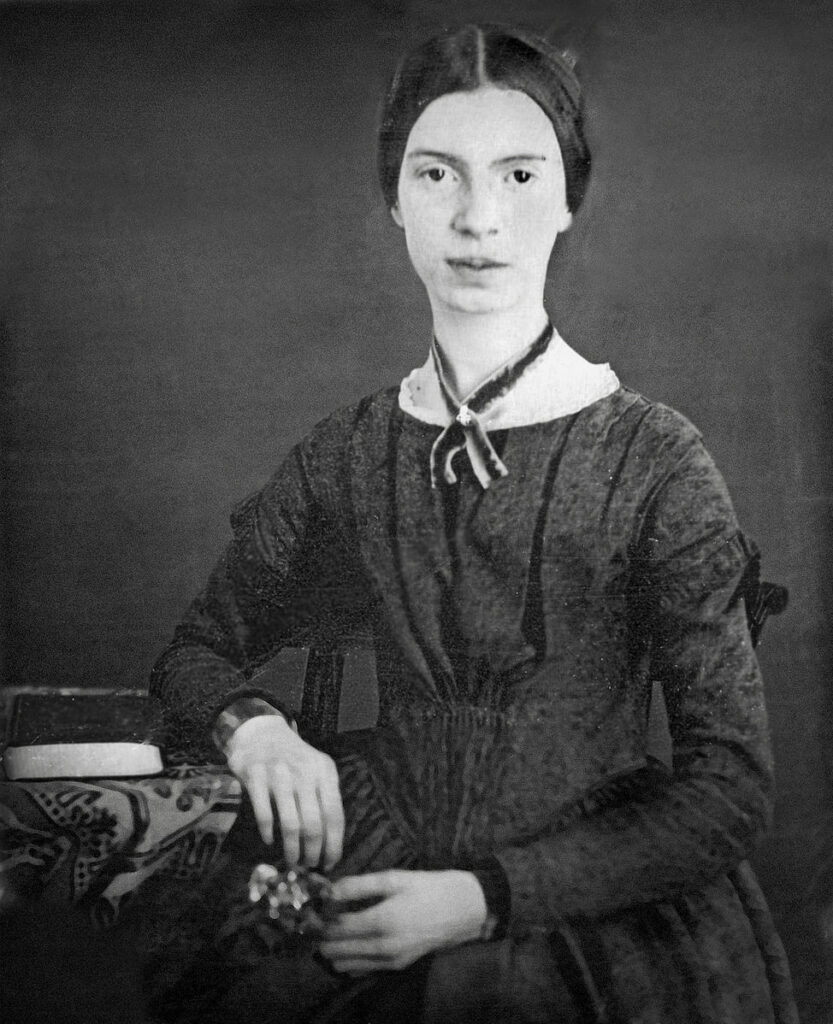

I’m reading 12/10/20 at 4:30 p.m. (ET) with poet/scholar Kathleen Ellis and others in celebration of Emily Dickinson’s birthday, obviously online. There are some who speculate that the reclusive E.D. would have loved the Internet age, but I can’t imagine she would have loved Zoom and all this showing up in a non-human way anymore than she wanted to show up in a here-I-am physical way.

Let’s remember for all the poems she wrote—1,800 plus—she never intended to publish them (and only ten found their way, anonymously, to the public eye in her lifetime). She sent them to people in letters, often accompanied by other things like a pressed flower or a dead insect, and for about a half-dozen years collected them in handmade folded-paper booklets. She wrote on backs of envelopes, pieces of newspaper, scraps, much the way I have for decades—mine out of necessity (only in these last years can I buy reams of blank paper or paints and materials). I came to art-making through pressed flowers—because they were free and so were the roof slates I mounted them on.

Let me make this clear. I’m no scholar or E.D. aficionado. That fact has troubled me most of my life—not specifically what I don’t know about her and her work, but what I don’t know or haven’t studied in any kind of deep or scholarly way about, what feels like, everything and everyone. And yet I have always felt energetically connected to so much—a puller and pusher of permutations, not any of it cast in exactness or exactitude, rightness or precision.

Living with her family of origin all her life, she had no real responsibilities other than caring for the “ailers” as time passed. Not a responsibility but a choice was the writing, and the correspondence, the gardening and pressing of flowers. She hung out in her bedroom, in the conservatory, in the gardens.

She spread her words like artworks across the page, dynamic visual structures minimized by print and containment. Breaths and rhythms, the curl and shape and plunk of letters, the dashes, both vertical and horizontal. Likely the publishing world of the day, its technology and its heartbeat, would try to box her into/onto the stiff, unyielding printed page. The first posthumous collections were stripped of all her quirks—the random capitals and erratic dashes, repetitives and abrupt drop-offs. Even with the stripping of her personal energetics, she shone through enough to keep the traveling words alive until they were restored to themselves. It’s like telling me I couldn’t wear mismatched socks or unmated earrings in five ear holes, long before people were doing either, that dancing must be choreographed or partnered, not wild and free, communal and solitary.

Emily had mentors. We all do. If someone influenced me, they influenced me in ways that impacted everything: like Lillian Wheaton, who went hunting into her nineties and had deep conversations with this then-vegetarian about everything; Doug Fletcher, the editor of the weekly newspaper in Houlton who trusted, and published, my first stumbling words, kind of prose poems (not that the phrase was part of my vocabulary); Randall Horton, who told me my “enjambments are a lyric all within themselves and how you juxtapose words creates the voluminous possibilities of language that many poets fail to recognize, let alone, execute”; Julia Walkling, who believed in my quirky facilitation style that let everybody’s voice into the room; Ashley Bryan, who unbeknownst to him, convinced me I was a solid interviewer of creatives; Queenesta Jones, who accepted me into a world that might have closed me out, and it made all the difference in every step I made after the age of 19; Henry Butler, who was/is love, complete and unconditional and eternal; Deb Dalfonso, who heard me read an essay decades ago and told me I was a writer, a “real” writer; Dori Sanders, whose drawling Southern voice still climbs into my ear to cheer me on with a “go, girl, go”; Ariel Gore, who took me on my first and only (so far!) road-trip reading tour; Chuk Williams, who taught me never to ask for permission, only forgiveness (if necessary), and filled me with every sport analogy there is, about possession and batting and so much more; Susan Ortiz, who danced me in; Kristbjorg Whitney, who answers the phone every time; and so, so many, many more.

Although I might have many more poems and essays, I can only think how much less I would be had I stayed in my childhood bedroom.

In the end, Emily tasked her only sister with destroying all her writing—poems and letters—when she died. As we gather Thursday, I have to wonder what she’s thinking now.

Discover more from Annaliese Jakimides

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.