I have been interviewing and writing about Maine makers for many years, and I am reminded that more and more of them are passing. I love the interview process, the crafting of questions, the research, the intimacy of the conversations. So much of this will be lost without a place in which to hold it, like crafting a vessel to transport the stories to another generation. DAVID MOSES BRIDGES passed in 2017 at the age of 54. I spoke with him in 2008 on his home turf.

ANCIENT BRIDGES

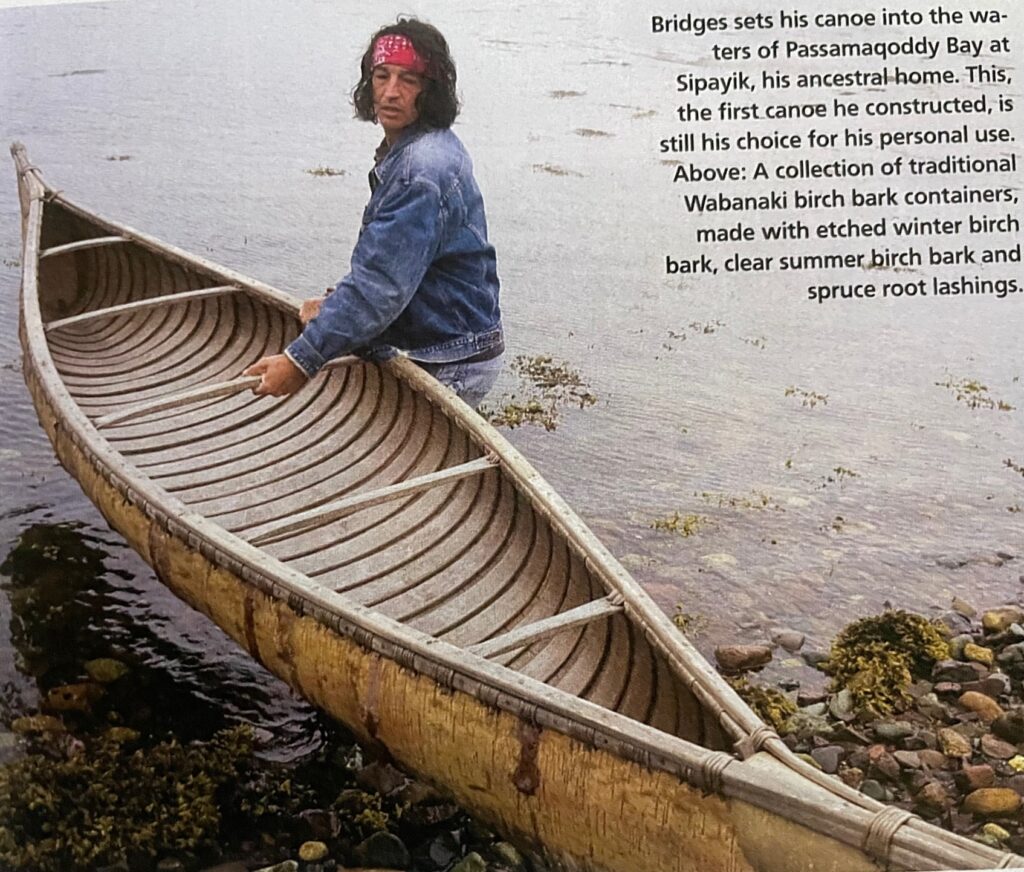

The birch bark canoe is the Passamaquoddies’ most ancient bridge across northern waters. When the art of creating these boats had nearly died, David Moses Bridges answered the call to bring them back to life.

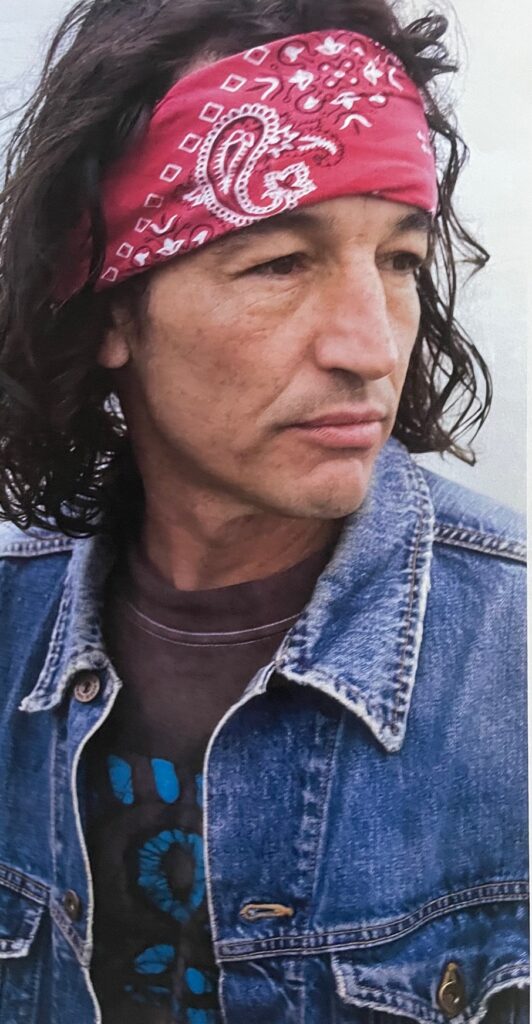

David Moses Bridges is a Passamaquoddy “bark” worker, a canoe maker, who explores the edges between the past and the future. He is a preservationist, preserving both the traditional ways of making birch bark canoes and the culture of this small, coastal tribe that was the point of first contact with the Europeans over 400 years ago.

In 1915, his great-grandfather Sylvester Gabriel, an old canoe maker, purchased the land the family lives on at Sipayik, with the intention that the family would grow. Although it did, the need to support that family as factory-made canoes took over the market resulted in Gabriel giving up canoe making. He made his last canoe in 1920 for the Plymouth Plantation tricentennial.

David Moses Bridges lives on that land today, and works in much the same way his great-grandfather did, felling large birch and cedar trees in the forest, hauling materials out on his shoulders, using the same simple tool kit to create everything needed to build the canoe—an axe, an awl, and three knives (crooked, sheath, and draw). Although today his great-grandfather’s kit travels with him for spirit, newer tools do the work.

Last summer he was an artist-in-residence at the Eiteljorg Museum in Indiana, where he built a wigwam, conducted workshops, and introduced the Wabanaki tribes to a broader audience since “the Midwest has learned about Native American indigenous people in history books, and they’re all riding horses, living in teepees or pueblos.” He has been involved in community and educational projects throughout Maine and Canada, as well as restoration and consultation projects around the country, including at the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in New York.

A delegate to the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, working with indigenous people around the globe, Bridges has also received awards from First Peoples Fund honoring native artists who “exemplify indigenous values of generosity, wisdom, respect, integrity, strength, fortitude, and humility.” He was the first recipient of the Maine Arts Commission’s Traditional Arts Fellowship. In 2004 he graduated from the University of Maine in Machias, magna cum laude, with a major in history, a minor in art.

Where did you grow up?

Although I lived away, this has been my home all my life. My mom was a nurse in Portland. She was actually one of the first Passamaquoddy to graduate from college. But I spent every summer here out on these islands, on the beach making rafts, out in the woods. This land is in my heart. It’s the most beautiful place in the world to me.

Your great-grandfather made canoes. Is that where you learned the traditional ways of bark work and canoe building?

No. He wasn’t making them anymore. No one was.

So how did you get interested?

My great-grandfather told me stories about making them. I knew that’s what I wanted to do since I was about 6. I tried to teach myself from this book [he flips through intricately detailed, dog-eared pages of The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of the North American Indians, a Smithsonian publication by Edwin Tappen Andey]. I couldn’t figure it out. Finally I went to the Marine Trades Center in Eastport to study boatbuilding and marine drafting. And I apprenticed with Steve Cayard, a very skilled non-Native builder.

What do you need to make a canoe?

To make a canoe in the traditional way—how I do it—the skill set involves being acutely aware of the environment you’re standing in. For example, I go out in late April, as soon as the ice breaks. There are no leaves on the trees, so I’m able to see for long distances across the lakes and through the forest. The buds on the birch are an emerald green color and I can identify stands. If I find one suitable for a canoe, I could take it then for a winter bark canoe, but usually I note it and come back in late June to gather that summer bark. You make a cut and it just separates from the tree then.

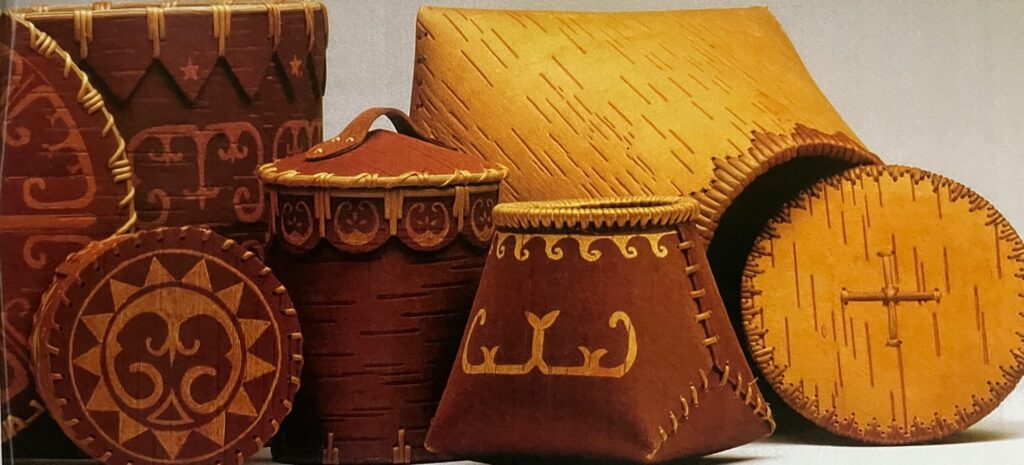

What’s the difference between winter bark and summer bark?

Winter bark is more for etching. The outer bark will cling to a thin rind of the inner bark and that will dry to a darker brown. It’s used more for containers and baskets. I’m the only Passamaquoddy from Sipayik making the etched winter bark baskets. And lately I’ve been experimenting with flat panel etchings, too, so I can get right to the etching part that I find so beautiful.

Do you only use birch?

No, I need cedar, white ash, maple, spruce for other parts. I don’t use any nails or screws, just wooden pegs and spruce roots for lashing.

It sounds to me like you’re spending an enormous amount of time gathering.

Oh, yeah, much more than building. I timed out a canoe one time. I had 1,400 hours of labor and about 500 were in the building.

And the labor, you carry everything out of the woods on your shoulders, your back, right?

I do. It’s very physically demanding work. As I look to the future—mine and the tribe’s—I’m looking at how restoration work, research, educational outreach, and advocacy also can be a stronger part of my work. Right now I’m compiling a short list of where all the birch bark objects are, their cultural provenance, their construction characteristics.

Do many tribes have bark workers?

The birch bark culture runs like a belt within a 500 mile range on either side of the 45th parallel—the southern edge of the boreal forest and the northern edge of the temperate. In the Siberian peninsula and all of the Lap cultures, even in northern Japan, they’ve all made use of birch bark. The birch bark culture is very complex in its simplicity.

What are you working on now?

Well, my schedule has been so busy that I didn’t build a canoe this year. I can’t get more than one made in a year anyway. But I’m excited about these kits I’m creating for kids. I received a grant from the New England Foundation for the Arts. I’m, of course, making the containers and baskets, the etchings, and I’m now exploring quill work on birch bark and moose hair embroidery, some of the old traditions I’ve been researching.

You’re like a hands-on historian.

They call it something—oh yeah, it’s applied anthropology. I believe through education, we can pass the history, the culture, forward. In this day it’s important to recognize our uniqueness and our connections. All the indigenous peoples have the same issues, with cultural loss, language loss. This winter I’ll be in South America, with indigenous people in Bolivia actually. We’re all more unified now. Passing all this on is really my work.

With a name like Bridges, do you see yourself as a link between the old and the new?

Who knows what they’ll sing about me at the end of my tour?

(Published in the original Bangor Metro; photo of Bridges by Leslie Bowman)

Discover more from Annaliese Jakimides

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.