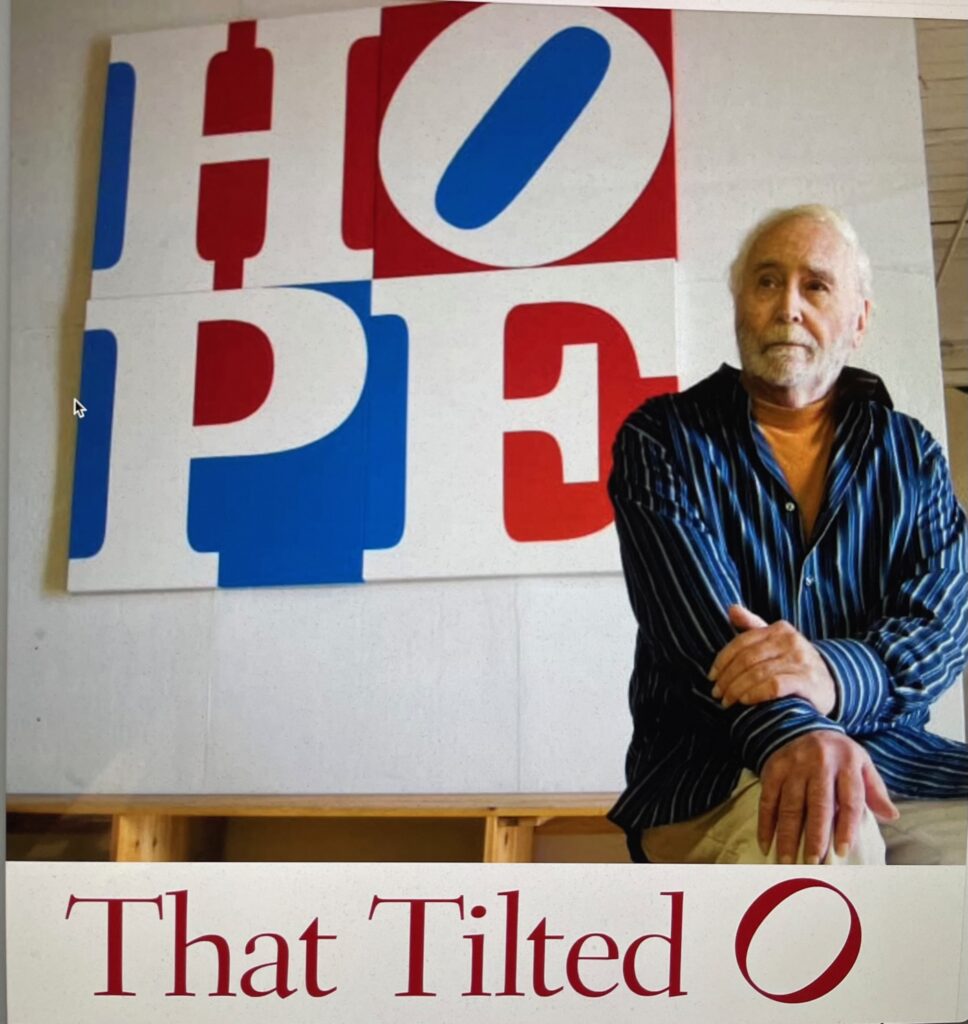

In 2008, in the summer before Barack Obama was elected president, I went out to Vinalhaven with my friend the photographer Leslie Bowman to interview artist Robert Indiana, who turned 80 in ’08—”a good omen for a man who changed the world with a tilted O” was the dek of the article. We took the ferry, stayed overnight on the island, and I rode a bicycle for the first time in decades.

At the time, Indiana had the following one-man exhibitions: Hard Edge at the Paul Kasmin Gallery; Robert Indiana: The Hartley Elegies at Bates College Museum of Art; Robert Indiana: The American Painter of Signs at the Museum Wiesbaden in Germany; and Robert Indiana at the Milano Pavilion of Contemporary Art in Italy.

This year Bob Keyes published a book about Indiana titled The Isolation Artist: Scandal, Deception, and the Last Days of Robert Indiana. Most people did experience and see Indiana in that way, not without cause, I’m sure. Recently, Leslie and were talking about the days with him on Vinalhaven, the interview, the photo shoot, and we both remember him as a fragile, sweet man, with a hunger to be seen that was fueled by something deeper than ego.

Robert Indiana passed in 2018, 10 years after I spoke with him for the first and only time.

by Annaliese Jakimides

Sculptor, painter, printmaker, and poet Robert Indiana lives quietly on Vinalhaven, rarely leaving the island he has called home since 1978 when he packed up a lifetime’s worth of goods from a five-story building in the Bowery in New York City, and moved it all into his beloved Star of Hope, the former Odd Fellows Hall on the main street in the center of town.

It is a world rich with history: his own work, including elementary school drawings and the amazing pastel portraits he made in high school; the work of artists like Ellsworth Kelly (the most important influence in his life, he says); Victorian furniture, chandeliers, whimsical stuffed animals that roar when you squeeze their ears and sing about love, should you choose to ask them. He has a garden and geese and a dog.

Overlooking the water, he works in an old sail loft, the island’s first theater from Civil War days, where he continues to create some of the most dynamic, iconic art made in America.

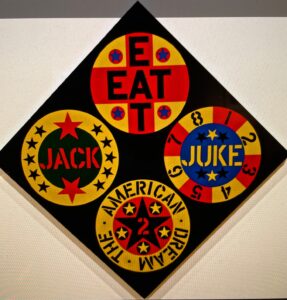

Symmetry, color, form, ordinary words—love, eat, die, peace, hope—and everyday numbers are obvious components of his enormous body of work. Both complex and accessible, he defies labels, both personally and professionally.

Born in Indiana, he grew up during the Depression, moving 21 times before he graduated at 17 as valedictorian of his class. He relinquished a one-year scholarship to art school to enlist in the Army Air Corp (subsequently, the U.S Air Force) so that he would eventually have five years of the GI Bill to pay for him to study art, the best decision, he says, he ever made. He graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, studied at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and at the University of Edinburgh, where he took courses in philosophy and botany, concentrating in poetry, before he settled in New York City in 1954.

Robert Indiana is responsible for what is likely the most recognized artistic image in the United States, perhaps the world—Love. He created it in 1964 for the Museum of Modern Art’s holiday card, the most popular card the MoMa has ever produced. The U.S. Postal Service sold over 333 million Love stamps—for which Indiana was paid $1,000. It has appeared on caps and posters, cups and any number of items, with and without his approval. In the 1960s a poster printed without a copyright sign opened it up to being the “most ripped off” artistic image ever, a situation not rectified for years.

Robert Indiana’s work can be found in many institutions around the world, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the New Orleans Museum of Art to the Shanghai Art Museum and the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation in London, as well as in parks and other public locations. His Love sculpture has been rendered in many languages, including Japanese and Hebrew, for “we all should experience love, and all the better in our own language.” The Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland is mounting a retrospective of Indiana’s work in the summer of 2009, with plans to erect his New York World’s Fair Eat sign on its roof “to brighten up Main Street.”

Are you equally a painter, a printmaker, a sculptor, and a poet?

Well, other things, too. I’m a dedicated archivist. I have a large library. Even as a young man, I had my own garden. When Mother and Father were worried about my being an artist, I had to think of alternatives. I thought I would like to have had a greenhouse and sold flowers. But probably more importantly, I observed that all the beautiful mansard-roofed Victorian mansions with towers were almost always the funeral parlors. So I had the fantasy that maybe I should become an undertaker. Maybe that would keep me from starving the way Mother and Father were convinced I would.

You moved around a lot when you were growing up. How did that shape your work?

It gave me a great amount to think about. This mother of mine insisted on moving just about every year. Before I was 17 years old, I had lived in 21 different houses. Her idea was the next house was going to be better than the last and usually it wasn’t that way. Throughout my youth, my dream house was this building—a Victorian with a tower and a mansard roof. I’ve lived out my dream come true on the island of Vinalhaven.

Why Vinalhaven?

I was a guest for one night of [Life] photographer Eliot Elisofon. We landed at the town pier. I walked up the ramp and the first thing I saw was the Star of Hope and within 10 days he had bought it for me at the “staggering” price of $6,000. It was 1969. The year we got to the moon I got to Vinalhaven.

Is the work you create here on Vinalhaven impacted by being here?

In no way. Except that [artist] Marsden Hartley lived here in 1938. I had never thought very much about him. His paintings of fishermen and seascapes and pine trees never grabbed me, but his military paintings… His friendship with a German officer killed in the First World War inspired what I consider my most impressive body of work, The Hartley Elegies.

That work like all of your work refuses to allow us to be passive observers.

One of my criteria for my own work is art should be memorable. It should be unforgettable. And I’m afraid there’s an awful lot of art that one can very easily forget. To me artists are probably more interesting than their paintings.

For years you kept meticulous journals about your work, sketching the pieces.

That’s simply how I kept a record of what I had done. I had no camera. I would like to have held on to all my work. I have been an archivist from the age of about 6, much to my mother’s consternation. I have drawings, scrapbooks, my writings, memorabilia. The hat that I wore as an art student at the Art Institute of Chicago is still hanging on the hook downstairs.

Did you know you would be an artist that early in your life?

I had absolutely no choice. My first art thief was in first grade in Morrisvile, Indiana. Morrisville is the home to John Dillinger, Public Enemy No. 1, you know. I’m sure that boy who stole my artwork was a Dillinger. I hope he was a Dillinger. My teacher saved the work, returned it to me. And at the end of the year, this young, inexperienced teacher who knew nothing about art asked if she might keep a couple of my drawings. She said she knew one day I would become a famous artist. So there it was. I could not disappoint her.

Did you study art in school?

Not at all until I went to Arsenal Tech in Indianapolis. It was a marvelous high school. At one point in time it had a student body of 7,000. When I was there, they had built another school. It was down to 4,000. There were 12 art teachers. By my senior year, I arranged my program so that out of an eight-hour day, I had six devoted entirely to art.

When you came to New York, you were identified as a Pop artist. Is that how you saw yourself?

None of us did. I consider myself “hard edge.” I’m a hard-edge painter. All my edges are crisp.

Edges and shapes. And a lot of numbers, too.

All that moving, you see. All relating to those 21 houses. My mother and father’s only amusement was their car. It was the middle of the Depression and we would jump in the car and go touring the countryside and check out all the houses we had lived in. Of course, there’d be House No. 1, House No. 2, House No. 3.

You’ve been called an American sign painter. You even included signs in your young work.

I am a painter of signs. One sign in particular influenced me. My father worked for Phillips 66. In those days all Phillips 66 stations were red and green. The stations, the gas pumps, the uniforms, the oil cans. The red and green of that sign against the blue sky is the reason that my principal love is red, blue, and green. I am fascinated by coincidences. That 66. And my father was born on the sixth day of the sixth month to a family of six members. When he left my mother he went west on Highway 66…

Is there a painting or sculpture you’ve done that you feel has significantly changed the course of your work?

Not particularly although love’s dominated most of my working life. Be it poetry, be it stamps, be it painting, sculpture, prints, love’s been the dominating factor.

What is it about love that continues to attract you as an artist?

It’s an overriding topic. It started with Mother, of course. I knew my mother loved me—I wasn’t absolutely sure about Father. And then, too, remember Hollywood movies were my babysitters. My mother would park me in a theater and I would watch thousands and thousands of movies, and you know what Hollywood movies are all about—love, love, love, you see.

What are you working on now?

Hope. I am mainly preoccupied with hope.

The Hope sculpture was first shown at the Democratic convention. Do you see your work as social commentary?

No, it’s autobiographical. The landscape of my own story. But of course some work does have something to do with a commentary on world situations. I witnessed 911. I saw the buildings collapse. I came back and did my Afghanistan painting. I put the flags on the front of the building. I was a hawk. Then along came Iraq and I became a dove.

Then here you are with Hope.

Yes, here I am with Hope. I have my fingers crossed. I hope that Hope will be as successful as Obama might be. That tilted O has been very busy.

ME ON THE FERRY, photo by Leslie Bowman

Discover more from Annaliese Jakimides

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.