THANKSGIVING NIRVANA? START WITH IRONED LINEN, ADD CREAMED ONIONS, BEETHOVEN, AND A FEW STRONG OPINIONS—AND DON’T FORSAKE THE PEAS.

BY ANNALIESE JAKIMIDES

No matter what anybody says, there is a “right” way to do Thanksgiving—and, of course, it’s my way. Actually, it’s my mother’s way, or a modified version thereof. Even when my walls were bare sheetrock and my floors painted plywood, I ironed the white linen tablecloth with the delicate, scalloped edges, and spread it over the kitchen table, along with the gold-and-green-striped cloth napkins, the creases sharp, precise. From an early age, my children set out the long-stemmed crystal goblets with the gold rims and our best “china,” my mother’s old, polished-for-the-holiday silverware, fragrant, tapered candles in earthenware (some things do change—my mother was a cut glass woman) candlesticks, and a vase of evergreen branches and dried lupine stalks (my version of the childhood carnations and baby’s breath).

Some may forever seek the storybook, Martha Stewart, Emeril Lagasse, or Oprah Winfrey holiday in which the image of perfect food in perfect places with perfect accompaniments to the perfect family (not loud, never arguing, no tears)—with a handmade, perfectly constructed centerpiece and coordinated placemats—but I suspect that, had I grown up eating macaroni and cheese out of the box for Thanksgiving, that’s what would feel “right.”

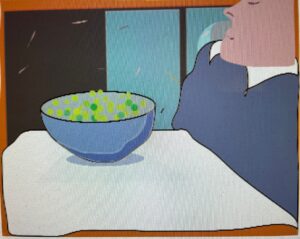

We eat peas at Thanksgiving because Uncle Hank hated every other vegetable and we only saw him, with his packed pipe and the thin wisps of hair stretched across his otherwise bald head, on that Thursday, once a year. (It is important to note that the first we is comprised of me as mother, and the second we is me as child.)

There is more: Boiled, creamed onions are my mother. So are candied yams with lots of brown sugar and swamps of butter, and a dish of pastel-colored mints I would otherwise never buy, never serve, and the salted cashews.

Mom played Mario Lanza and Billy Eckstine, some Beethoven to appease Dad. I play Etta James and Arnett Cobb, always Kenny Loggins singing “Please Celebrate Me Home,” and Beethoven’s “Fur Elise” because, incongruously, my youngest child loved it and continued to love it along with the hardest-edged, toughest rap.

For the past few years, I’ve been doing that Thanksgiving-in-the-wrong-place thing—wrong food, no music, few people. The kids now live too far away and can’t make it home and so my friends invite me to Patten, to Bar Harbor, to Hulls Cove, Lincoln, Pembroke, and Levant.

I used to say that once the time had come that I couldn’t gather my children “home for the holidays,” I’d just get on the bus, go somewhere new and seek an adventure, get a motel room, eat out, see a show, walk a beach, be open to the whatevers of life. It sounded wild and wonderful and filled with discovery.

And this year I am rolling my suitcase up Main Street to the Greyhound, but I’m not headed into the great unknown.

I’m headed smack into the belly of a family as big and raucous and funny as my childhood one. I knew that soon my children would meld their worlds, their traditions, with someone they love and who loves them. It begins with my oldest son. He’s engaged to a great woman—and a great family, who laughs and dances, is loud, loves music and talks (even disagrees, can shout), and loves my son. I am so happy that all the human elements are in place, I don’t care what they eat. I’m coming.

Annaliese Jakimides is thankful to have been part of the extraordinary team that conceived the original Bangor Metro magazine, in which this essay was published.